[ad_1]

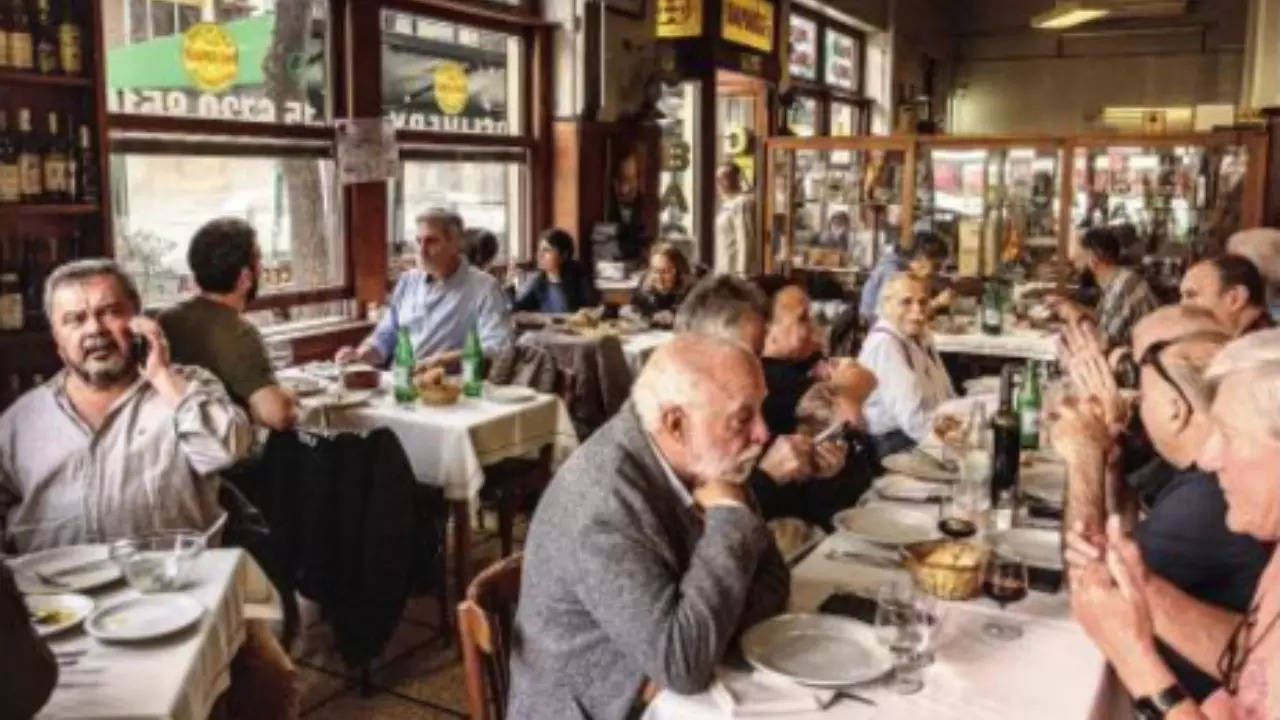

BUENOS AIRES: Wineglasses clinked in an art nouveau culinary gem basking in its restored splendour. It was tasting night in the more than century old coffeehouse turned restaurant at the old Buenos Aires zoo, as beet tartare, pan-seared squid and a perfect rib-eye floated out of the kitchen, chased by a velvety chocolate mousse.

“We are betting hard on the opportunity of the food scene in Argentina,” said Pedro Diaz Flores, co-owner of Aguila Pabellon restaurant — the 17th food venture he has opened in Buenos Aires in the past 18 months. In Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital, a world-class culinary scene is flourishing. That would not necessarily be news if it were not for the fact that Argentina is in the middle of an extraordinary financial crisis. Inflation is at over 114% —the fourth highest rate in the world — and the street value of the Argentine peso has crumbled, dropping about 25% over a three-week period in April.

Yet it is the peso’s downfall that is fuelling the restaurant industry’s upswing. Argentines are eager to get rid of the currency as quickly as they can, and that means the middle and upper classes are going out to eat more often — and that restaurateurs and chefs are plunging their revenues back into new restaurants. “Crises are opportunities,” said Jorge Ferrari, a restaurant owner.

Buenos Aires, which has been trying to promote its culinary scene, has been tracking the volume of plates sold at a sample of restaurants each month since 2015. The recent numbers, for April, show that restaurant attendance is at one of its highest levels, and 20% higher than at its highest point in 2019, before the pandemic. The boom is a facade. In much of the country, Argentines are scraping by and hunger is on the rise. In wealthier circles, the rush to go out is a symptom of a shrinking middle class that, no longer able to afford bigger purchases, is choosing to live in the here and now because their money may not be worth anything in the future. “It is consumption for satisfaction — happiness in the moment,” Ferrari said.

“We are betting hard on the opportunity of the food scene in Argentina,” said Pedro Diaz Flores, co-owner of Aguila Pabellon restaurant — the 17th food venture he has opened in Buenos Aires in the past 18 months. In Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital, a world-class culinary scene is flourishing. That would not necessarily be news if it were not for the fact that Argentina is in the middle of an extraordinary financial crisis. Inflation is at over 114% —the fourth highest rate in the world — and the street value of the Argentine peso has crumbled, dropping about 25% over a three-week period in April.

Yet it is the peso’s downfall that is fuelling the restaurant industry’s upswing. Argentines are eager to get rid of the currency as quickly as they can, and that means the middle and upper classes are going out to eat more often — and that restaurateurs and chefs are plunging their revenues back into new restaurants. “Crises are opportunities,” said Jorge Ferrari, a restaurant owner.

Buenos Aires, which has been trying to promote its culinary scene, has been tracking the volume of plates sold at a sample of restaurants each month since 2015. The recent numbers, for April, show that restaurant attendance is at one of its highest levels, and 20% higher than at its highest point in 2019, before the pandemic. The boom is a facade. In much of the country, Argentines are scraping by and hunger is on the rise. In wealthier circles, the rush to go out is a symptom of a shrinking middle class that, no longer able to afford bigger purchases, is choosing to live in the here and now because their money may not be worth anything in the future. “It is consumption for satisfaction — happiness in the moment,” Ferrari said.

[ad_2]

Source link