[ad_1]

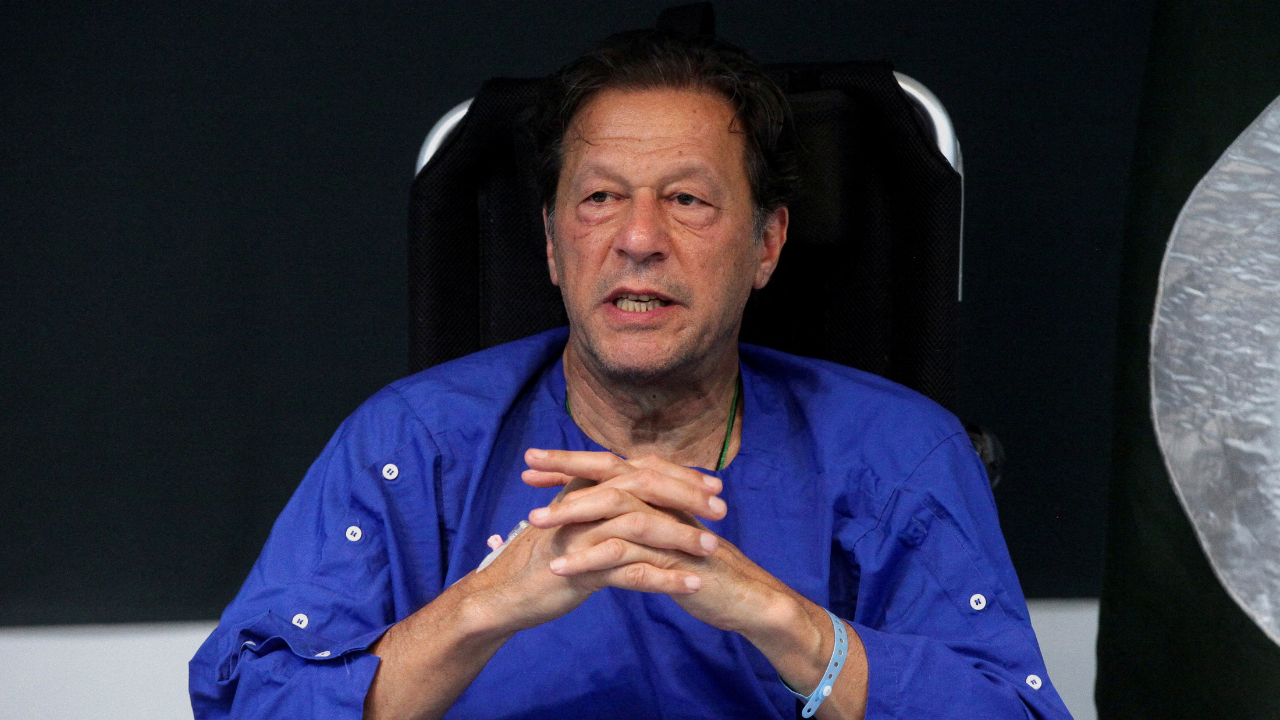

ISLAMABAD: Former prime minister Imran Khan has gone from being the chosen one to a thorn in the side of Pakistan’s military — long considered the nation’s political power brokers.

His arrest this week — after delivering another broadside against a senior intelligence officer — marks an escalation in the duel between Khan’s staggering popular appeal and the army’s vast influence.

“What he has done is say the quiet bits out loud and has broken down some of the taboos around directly criticising Pakistan’s establishment, and its military specifically,” said analyst Elizabeth Threlkeld at the US-based Stimson Center.

“Now that that genie is out of the bottle it’s proving quite difficult — if not impossible — to put it back in,” she told AFP.

Pakistan’s military has staged three coups since independence in 1947, ruled the nation directly for more than three decades, and continues to wield huge influence in domestic politics.

When Khan rose to office in 2018 after winning over an electorate weary of the dynastic politics of Pakistan’s two major parties, many political leaders and analysts said it was with the blessing of the military establishment.

Likewise, his ousting last April via a parliamentary no-confidence vote came only after a falling out with the top brass of the world’s sixth-largest army.

The relationship began to sour following Khan’s push for more of a say in foreign policy, as well as a stand-off with the military over a delay in rubber-stamping the appointment of a new intelligence chief.

But in his campaign to return to power, the 70-year-old has broken with political convention and directly criticised both retired and serving officers.

Widely popular Khan “doesn’t feel beholden to the same benefactors” previous prime ministers might have, said Threlkeld.

After the former cricket superstar was ousted, his successor Shehbaz Sharif appointed a new army chief — widening the rift with Khan by selecting a man who had famously fallen out with him while he was in office.

Sharif’s government also drafted new regulations to shield the military from criticism.

In February, Islamabad proposed punishing those who ridicule the army with up to five years in prison. In March, media reports suggested they were also taking measures to rein in critique on social media.

Nonetheless, Khan steadily ratcheted up his attacks over the past year, culminating in explosive allegations following a November assassination attempt, which saw Khan shot in the leg while on the campaign trail.

Khan alleged a senior intelligence officer, Major-General Faisal Naseer, was in cahoots with Sharif in plotting the attack.

“Perhaps he thought that by building pressure on the army, by criticising the army, the army will pull back from supporting the present government,” said analyst Hasan Askari.

“It’s a risky strategy,” he told AFP.

Khan has never offered proof of his claims regarding the assassination plot.

This weekend, he repeated the allegations, causing the army’s public relations wing to raise the stakes with a rare public rebuke, branding his remarks “fabricated and malicious”.

A day later, Khan was swarmed by paramilitary Rangers and arrested at Islamabad High Court as he appeared to face a graft case.

“The timing of the arrest is striking,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center.

“The senior army leadership is uninterested in repairing the rift between itself and Khan, and so with this arrest it’s likely sending a message that the gloves are very much off.”

Supporters of Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party have raised the stakes by attacking military targets — torching the residence of the corps commander in Lahore and attacking the entrance to the army’s headquarters in Rawalpindi.

In Peshawar, a mob razed the Chaghi monument — a mountain-shaped sculpture honouring the location of Pakistan’s first nuclear test, while several memorials to service members killed on active duty were also vandalised.

On the streets of major cities, social media footage showed some PTI supporters attacking army vehicles on security duty, attempting to beat soldiers with sticks.

“The long-term future of democracy at this stage appears to be very uncertain in Pakistan,” Askari warned.

His arrest this week — after delivering another broadside against a senior intelligence officer — marks an escalation in the duel between Khan’s staggering popular appeal and the army’s vast influence.

“What he has done is say the quiet bits out loud and has broken down some of the taboos around directly criticising Pakistan’s establishment, and its military specifically,” said analyst Elizabeth Threlkeld at the US-based Stimson Center.

“Now that that genie is out of the bottle it’s proving quite difficult — if not impossible — to put it back in,” she told AFP.

Pakistan’s military has staged three coups since independence in 1947, ruled the nation directly for more than three decades, and continues to wield huge influence in domestic politics.

When Khan rose to office in 2018 after winning over an electorate weary of the dynastic politics of Pakistan’s two major parties, many political leaders and analysts said it was with the blessing of the military establishment.

Likewise, his ousting last April via a parliamentary no-confidence vote came only after a falling out with the top brass of the world’s sixth-largest army.

The relationship began to sour following Khan’s push for more of a say in foreign policy, as well as a stand-off with the military over a delay in rubber-stamping the appointment of a new intelligence chief.

But in his campaign to return to power, the 70-year-old has broken with political convention and directly criticised both retired and serving officers.

Widely popular Khan “doesn’t feel beholden to the same benefactors” previous prime ministers might have, said Threlkeld.

After the former cricket superstar was ousted, his successor Shehbaz Sharif appointed a new army chief — widening the rift with Khan by selecting a man who had famously fallen out with him while he was in office.

Sharif’s government also drafted new regulations to shield the military from criticism.

In February, Islamabad proposed punishing those who ridicule the army with up to five years in prison. In March, media reports suggested they were also taking measures to rein in critique on social media.

Nonetheless, Khan steadily ratcheted up his attacks over the past year, culminating in explosive allegations following a November assassination attempt, which saw Khan shot in the leg while on the campaign trail.

Khan alleged a senior intelligence officer, Major-General Faisal Naseer, was in cahoots with Sharif in plotting the attack.

“Perhaps he thought that by building pressure on the army, by criticising the army, the army will pull back from supporting the present government,” said analyst Hasan Askari.

“It’s a risky strategy,” he told AFP.

Khan has never offered proof of his claims regarding the assassination plot.

This weekend, he repeated the allegations, causing the army’s public relations wing to raise the stakes with a rare public rebuke, branding his remarks “fabricated and malicious”.

A day later, Khan was swarmed by paramilitary Rangers and arrested at Islamabad High Court as he appeared to face a graft case.

“The timing of the arrest is striking,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center.

“The senior army leadership is uninterested in repairing the rift between itself and Khan, and so with this arrest it’s likely sending a message that the gloves are very much off.”

Supporters of Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party have raised the stakes by attacking military targets — torching the residence of the corps commander in Lahore and attacking the entrance to the army’s headquarters in Rawalpindi.

In Peshawar, a mob razed the Chaghi monument — a mountain-shaped sculpture honouring the location of Pakistan’s first nuclear test, while several memorials to service members killed on active duty were also vandalised.

On the streets of major cities, social media footage showed some PTI supporters attacking army vehicles on security duty, attempting to beat soldiers with sticks.

“The long-term future of democracy at this stage appears to be very uncertain in Pakistan,” Askari warned.

[ad_2]

Source link